No products in the cart.

Jewish.Shop - Judaica, Gifts, Art, Jewelry and Much More

-

Tallit & Tefillin Bag – Star of David “In your grace I trusted” – Gray and blue

Rated 5.00 out of 501$73.00$83.00 -

Tefillin bag / Tefillin Briefcase – with strap

Rated 5.00 out of 502$23.00$30.00 -

Natlah: Elegant Polyresin Natlah 13.5cm- brown

Rated 5.00 out of 501$25.29$34.29 -

Modern Kiddush Cup “Jerusalem”

Rated 5.00 out of 501$65.00$91.00 -

Tallit “Sapir” – with Blue stripesTallit

Rated 5.00 out of 501$83.00 – $121.00 -

Tallit Clips “Jerusalem” (Nickel)

Rated 5.00 out of 501$14.00$23.00 -

Modern Candlesticks For Shabbat “Rimonim”

Rated 5.00 out of 501$40.26$64.05 -

Tallit & Tefillin Bag – Silver Choshen on impela fabric

Rated 5.00 out of 501$66.00$76.00 -

Tefillin (from large cattle) – “HOD” ⋆ Mehudar A [Ari/Chabad font]

Rated 5.00 out of 501$746.00 – $756.00 -

Plastic Tefillin boxes – black – Includes mirror

Rated 5.00 out of 501$11.00 -

Gentle polyrazine Natlah in a unique red-pink-white shade.(13.5 cm)

Rated 5.00 out of 501$25.29$34.29 -

Silver Kiddush Cup “Leaves” (Plated)

Rated 5.00 out of 501$68.25$151.20 -

Modern Kiddush Cup “Turquoise”

Rated 5.00 out of 501$60.52$77.70 -

Mesh Tzitzit – Mesh Fabric Tallit Katan (V-neck)

Rated 5.00 out of 501$7.00 – $10.50 -

Tallit Clips “Star of David Hadar”

Rated 5.00 out of 502$14.00$23.00 -

Modern Candlesticks “Turquoise Shabbat”

Rated 5.00 out of 501$40.26$64.05 -

Tallit & Tefillin Bag – Halved Impala fabric, with a decorative pomegranate tree branch

Rated 5.00 out of 501$66.00$76.00 -

Tefillin Dakkot “Noy” ⋆ Peshutim Mehudarim [Ari/Chabad]

Rated 5.00 out of 501$386.00 – $387.00 -

Mezuzah Case – Plastic Mezuzah with Screw 10cm- Clear with Silver Shin

Rated 5.00 out of 501$3.49$12.49 -

Tikfilin – Black/Transparent Tefillin bag

Rated 5.00 out of 501$19.00 – $29.00

Jewish.Shop – Judaica Products Shipped Worldwide

Celebrating your faith can be just as important as practicing it. Jewish.Shop offers everything you need to be a devout person and more. From Judaica and ceremonial necessities to jewelry, art, and gifts, you can find it all in one place- Jewish.Shop!

Everything is authentically made and follows kosher guidelines. Crafted and assembled in Yavne’el, Israel, we ship all our products anywhere in the world, serving the global Jewish community.

Browse our site to see all that Jewish.Shop can offer you and your journey of faith!

Fast and Reliable Shipping from the Source

All the products from Jewish.Shop come from Israel, the country in which our faith originated. Everything is carefully created to serve the purpose of guiding and elevating your religion. Since Israel is such an extraordinary place for the Jewish faith, we source all our products here. That way, everyone has access to beautifully made Judaica that comes directly from the source of our faith.

We ship our merchandise from the small colony of Yavne’el, Israel. As one of the oldest rural Jewish communities in Israel, Yavne’el sits near the Sea of Galilea. It is from this small village with such deep historical significance that we ship the products from our Judaica store all over the world.

You can receive authentic Israeli products within 20 days—no matter where you are in the world, Jewish.Shop gives everyone access to authentically sourced Jewish necessities.

Everything Kosher

We ensure that all products, from tefillin to menorahs, are kosher so that even the most steadfast practicing Jew can be comfortable buying from Jewish.Shop. Following kosher guidelines is a serious practice for many, and we want every practicing Jew to have the opportunity to purchase religious necessities from the Holy Land of Israel.

Shop jewelry, kippahs, shtenders, and more- all products receive the care and attention needed to make incredibly beautiful kosher products.

Shop Tallit

Jewish.Shop has all you need for your tallit. You can purchase an entirely new one or look for a new clip or tzitzit. We understand the significance of wearing a tallit when it comes to practicing your faith. That is why we dedicate ourselves to selling the most high-quality tallit to you, including all other necessary aspects, like the tzitzit, clip, or atarah. You can have confidence in your tallit- one of the most essential accessories to practicing Judaism.

Shop for all things tallit in our Judaica store. You can browse by price, size, or rating. No matter what you choose, your prayer shawl is made from the finest materials and shipped from the sacred land of Israel.

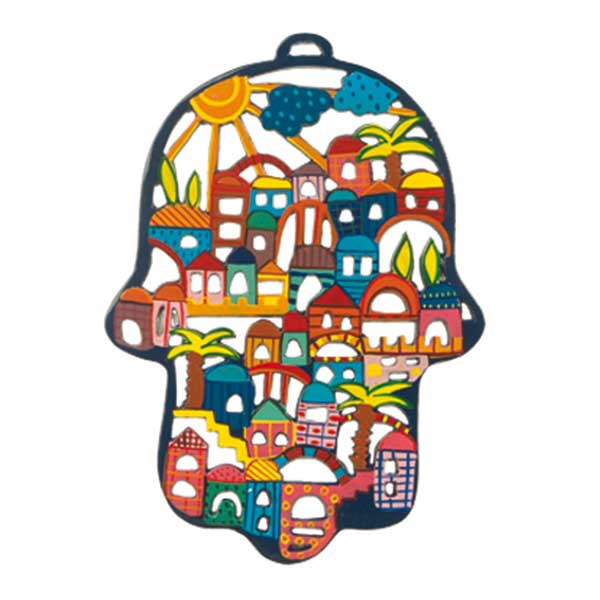

Shop Mezuzah

Fulfill the mitzvah by purchasing a beautiful Mezuzah from Jewish.Shop. Finding the perfect mezuzah for your home should not be difficult. Therefore, we offer a variety of meaningful boxes to hold the scrolls. You can surely find an elegant mezuzah that matches the appeal of your home.

The mezuzah cases are categorized based on their style so that you can find what you want easily. Browse everything from metal and wooden cases to painted and embroidered holders.

However, we don’t stop with the cases. Jewish.Shop also offers mezuzah scrolls. Purchase holy scripture that comes directly from the country in which it all began.

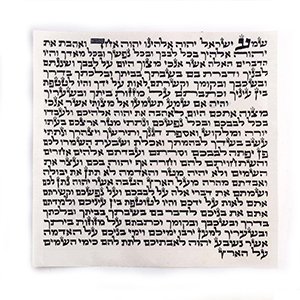

Shop Tefillin

For some of the stricter practicing Jews, you use the tefillin every weekday. It is crucial to have high-quality tefillin boxes and straps, as well as the materials to maintain them. Jewish.Shop creates the finest, most highly sought after tefillin.

Our tefillin boxes come in simple colors: black, silver, gold, or ivory. You can choose whichever you favor. Then, you should find the proper straps. We provide only three straps to choose from because the search for complete tefillin should be simple and straightforward. If you want more, you can also look through our tefillin bags and markers that uphold the box’s high quality.

Shop JLife and Home & Decor

Jewish.Shop carries all the essentials for bar mitzvah, mezuzah, and everything in between. Being Jewish is an integral part of your identity, so you should have the products that strengthen your faith. Shop in our JLife section for your daily items that influence religion. We have the kippahs, scarves, books, and candles that serve as reminders of G-d’s great love.

Spruce up your home, too, with different biblical significant pieces that also remind you of your faith. Browse through towels, table runners, and more so that you can make family dinners and traditional meals even better.

Shop by Holiday

Preparing for the next big holiday can be a stressful event. Get all your materials right here at Jewish.Shop to add a more sacred element to the festivities. Since everything we sell is crafted in the Holy Land, you can be sure to have a holy and more spiritual celebration.

Find necessities for all the major holidays you celebrate, like:

Browse through candles, candle holders, menorahs, and more. We have all that you need to make the next Jewish holiday a success. Buying from us means buying from Israel. Create an even more sacred atmosphere with a Shabbat candle holder from Israel or a Shofar from the Holy Land for Rosh Hashanah.

Jewish.Shop Has All You Need

From holiday essentials to everyday items, buy from Jewish.Shop. We ship our high-quality products directly from Israel to your front door. No matter where you are in the world, we make sure that you efficiently get the products. On-time shipping, safe payment, and authentically made merchandise are what we stand for.

For the next big holiday or gathering, you can count on Jewish.Shop for elegantly crafted items that come straight from Israel. We take pride in shipping all our products from the beautiful community of Yavne’el.

Even if there is no big holiday nearby or a significant family event, you can still purchase charming Jewish.Shop products to spruce up your home. Browse and shop in our Israeli Judaica store and discover ways to strengthen your faith today!

A Judaica store is a store that specializes in selling Jewish-themed items, such as ritual objects, books, art, and other items that are related to Jewish culture, history, and religion. Some Judaica stores sell items that are used in Jewish religious ceremonies and rituals, such as tallitot (prayer shawls), kippot (skullcaps), tefillin (phylacteries), and mezuzot (small scrolls containing Hebrew prayers). Others sell items that are related to Jewish culture and history, such as books, art, music, and other items.

Judaica stores can be found in many Jewish neighborhoods and communities around the world, and they often serve as important gathering places for members of the Jewish community. Many Judaica stores also offer classes, lectures, and other educational events to help people learn more about Jewish culture and traditions. If you are looking for items related to Jewish culture or if you are interested in learning more about Judaism, a Judaica store may be a good place to start.